The Origins

Orogenic, Archaeological and Etymological Notes on La Faula

La Faula is the name of Casa Faula, today Casali Faula. The Friulian name Prat de Faule – the field of the Faula – was first recorded in 1550, and the people who owned it were referred to as Chei de Faule – those of La Faula.

Originally it was claimed that the word Faula derived from fagula, the beech grove. Other etymologists of the Friulian idiom assert that Faula instead derives from the Latin word fabula, which became faule in Friulian. Whilst in Latin fabula means "tale" – i.e., something recounted – the Friulian faule is made to derive from the verb fevelâ – to speak, to talk – and therefore means something spoken. It could refer to the fact that the property was, at some stage, assigned through a verbal contract.

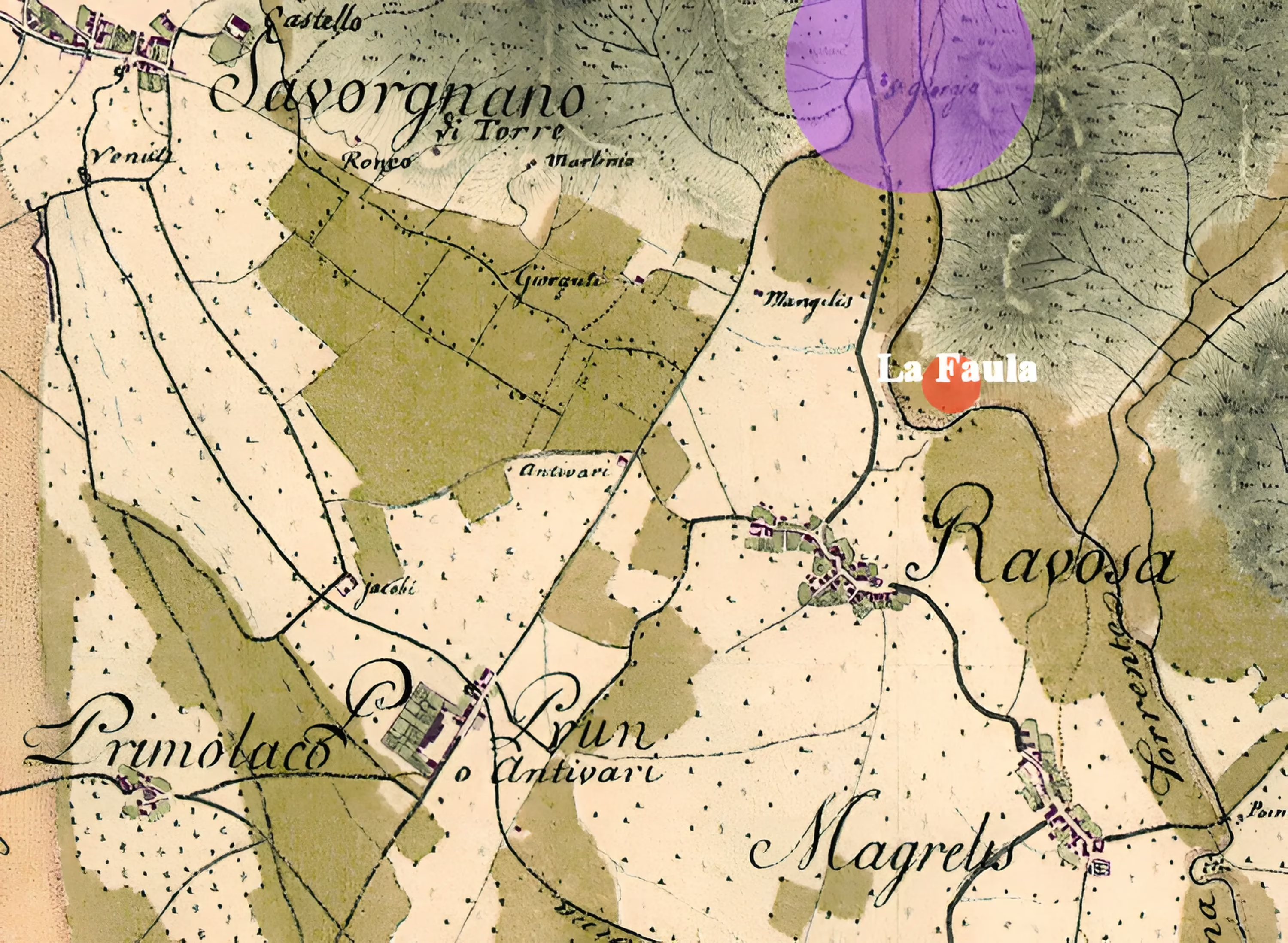

La Faula is located on the north-eastern shore of the Malina torrent, opposite the village of Ravosa. Although Ravosa was first recorded in documents dating back to April 1252 ( 'usque ad collum Spia et paludem Ravosa' – all the way to the hill and the marsh Ravosa looks at), archaeological findings trace its origins to the Roman Age.

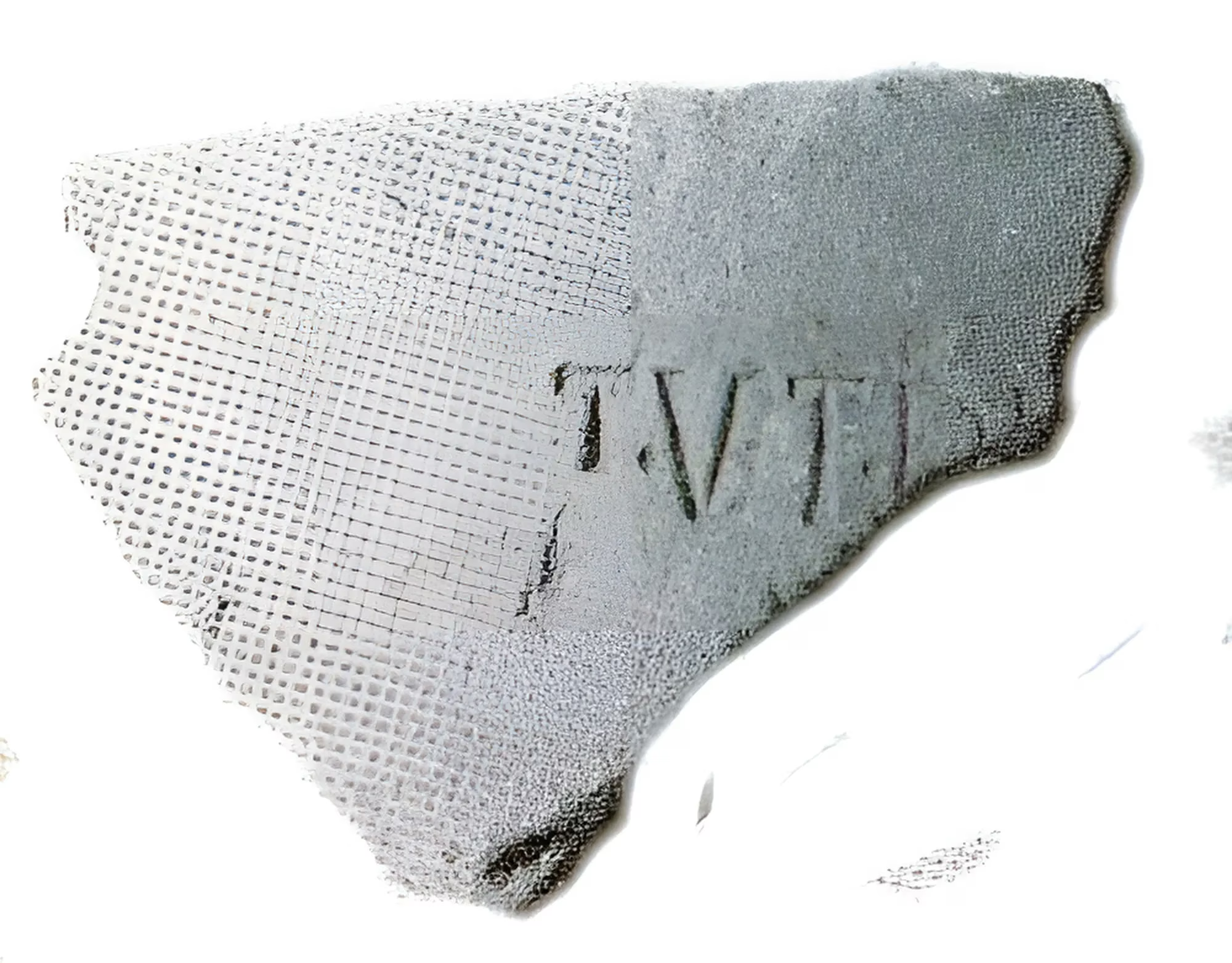

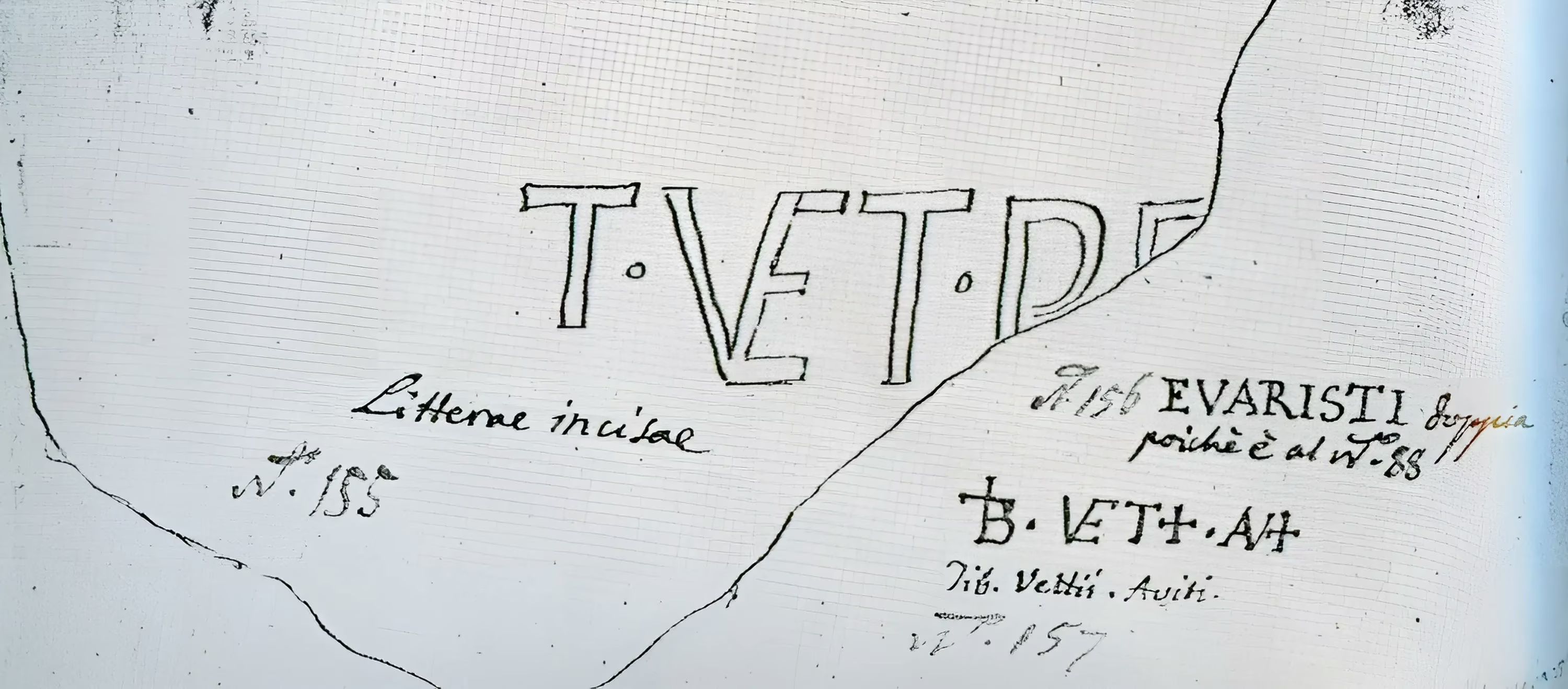

The small vineyard neighboring the one at La Faula was terraced with picks and shovels between 1927 and 1930.

During its shaping, a Roman dwelling was unearthed.

Although the vineyard belonged to Agostino Calligaris, a small farmer from the neighboring village of Magredis, it was the local General Practitioner, Doctor Emilio Sartorelli – who owned a nearby vineyard – who in 1931 donated the various pieces of Roman pottery and building materials to the Museum of Udine.

Studies of the arrangement of the agricultural fields with regard to the incline of the land, the water drainage, and canalization systems prove that the countryside still reflects the rigid rules set out by the Roman centuriation system of agricultural land.

We may, therefore, infer that very early settlements might have existed where the house of La Faula sits today.

The entire area is raised with respect to the Malina riverbed. The river banks were only built during the late 1960s.

Until then, during periods of heavy rain, the river flooded all the surrounding land.

During a soil test carried out in the 1990s by Regional agricultural technicians, it was found that behind the barn, a brick furnace – now covered by over a meter of soil – occupied an area of at least 20 m².

This type of furnace was generally placed on a raised area near a spring or stream.

Several are to be found at the foot of the hills along the road from Ravosa to Attimis and scattered throughout the Friulian hills at the foot of the Alps.

Geologically, these hills were seabeds raised by orogenetic movements. The topsoil is heavy clay, ideal for brick making. The hills also provided an unlimited supply of wood to fire the kilns. In Roman times, bricks and tree trunks were transported to the south of the region to help build the port city of Aquileia.

La Faula sits at the foot of the first range of hills between the Friulian plain and the mountains.

From 1550 to 1588, the hill was recorded on maps and land registers as Gion, a name deriving from the Lombard gahagi – "banned land" – because it formed part of a feudal property.

It is likely that the area belonged to one of the various Germanic lords: Uldrich of Treffen (1160–82), who lived in the Castle of Partistagn (from the German behrt stein – "brilliant stone") in Borgo Faris; or the Marquis of Moosburg in the Castle of Attem (from the Gaelic ati- and tem – "place above the water", today’s Attimis), built between 1250–60; or Lord Uldrich of Hausberg in the Castle of Cucagna, overlooking Faedis, first recorded in 1186. All these castles were within a range of 8 km or less from La Faula.

During the Middle Ages, the area around La Faula was likely wooded.

The Visigoths had established the right to graze pigs on acorns. One thing is certain: whatever the land yielded – wood, hay, cereals, pulses, or wine – most of the produce went to the Lords, Abbots, or Prioresses who owned the land.

Until well after the end of the Second World War, most of the land in Friuli belonged to a few landowners.

Only with the introduction of agricultural reforms did sharecroppers ( sotans in Friulian), farm tenants (who paid rent in kind), peasants, and laborers become either independent small farmers or migrate in search of work elsewhere.